If we have the courage and tenacity of our forebears, who stood firmly like a rock against the lash of slavery, we shall find a way to do for our day what they did for theirs.

~Mary McLeod Bethune

I’d never been to Alabama before our trip in November 2024. Actually I’ve hardly spent any time in the South as an adult, though I don’t imagine it as a monolithic place. Brief visits to Austin, Texas, Charleston, South Carolina, Savannah, Georgia, and Jonesborough, Tennessee, confirmed for me the diversity of the region. Another post ponders a formative time for me and my family in North Carolina.

For the five-day Living Legacy Pilgrimage, we arrived at Shuttlesworth Airport in Birmingham on November 13. The airport and our hotel were in the northern part of the city. Prior to our trip, I had read much of journalist Diane McWhorter’s book, Carry Me Home, so I knew that the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth (1922-2011) was a courageous and committed leader relentlessly insisting on Black civil rights in Alabama and beyond. Officials didn’t name the airport for him until 2008, though. We then took a shuttle from the airport along Richard Arrington, Jr. Drive to our hotel. Along the way, I looked up Richard Arrington: another amazing leader and the first Black mayor of Birmingham. In 1966, he earned his doctorate in zoology at the University of Oklahoma, returning to Miles College in Birmingham to serve as an administrator before he began his long service in government. Our first visit, to the Historic Bethel Baptist Church, was also north, in an area called Collegeville. Our bus waited at railroad tracks for a lengthy train to pass before our arrival at the church.

Bethel Baptist is small in size but historically huge in impact. Rev. Shuttlesworth was its pastor from 1953 to 1961. After his departure from Bethel, he continued to lead civil rights actions in Birmingham while living in Cincinnati. Bethel was bombed three times by white supremacists, in 1956 (including the parsonage), 1958, and 1962, because it was an important node in efforts to integrate buses, schools, and public accommodations. I won’t enumerate the dogged and brave actions of Black people in Birmingham; these efforts are catalogued and described in detail elsewhere. But what strikes me is the faith and the strategizing by Black folks to push and keep pushing toward seemingly out of reach goals in the face of white terrorism and hostility. Again and again on this trip, I was in awe of how people handled their fear and kept on toward their vision despite beatings, bombings, and murders. And they did it when not many people supported them, so not only did they have to resist massively violent responses from authorities, they also tried to convince folks to join them in protests.

Leadership

While we were encouraged by the pilgrimage organizers to focus on the civil rights era, it was nearly impossible to avoid making connections between that time and now, post-election of #47. The book that I was reading on our trip was Steve Phillips’ How We Win the Civil War: Securing a Multiracial Democracy and Ending White Supremacy for Good, which he published in 2022, with a cogent preface written for the second edition in the spring of 2024. In other words, #47 hadn’t been elected yet when he wrote that preface, but he encourages us to find “imagination to meet the moment.” (xxiii) In Part Two of his book, Phillips lays out “How We Win” against the still-extant Confederacy. He posits four crucial steps:

- Invest in Level 5 Leaders

- Build Strong Civic Engagement Organizations

- Develop Detailed, Data-Driven Plans

- Play the Long Game

Thinking about civil rights leaders, I was interested to read about Phillips’ profile of Level 5 leaders, people who move organizations from good to great. He cites Aldon Morris’ research on civil rights leaders, Origins of the Civil Rights Movement (1986). Morris “described effective leaders as those who ‘engage in organization-building, mobilizing, formulation of tactics and strategy, and articulation of a movement’s purpose and goals to participants and the larger society.'” (169) Another writer he cites, Jim Collins, who wrote Good to Great, was a little more specific: “Level 5 leaders display a powerful mixture of personal humility and indomitable will. They’re incredibly ambitious, but their ambition is first and foremost for a cause, for the organization and its purpose, not themselves… [motivating] the enterprise more with inspired standards than inspiring personality.” (167) (Emphasis is mine.) Our pilgrimage was, in a way, an homage to cause-driven leaders such as Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Hosea Williams, CT Vivian, James Reeb, Jimmie Lee Jackson, Jonathan Daniels, Amelia Boynton, James Forman, Bayard Rustin, and, yes, Fred Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Level 5 leaders need strong civic engagement organizations with detailed plans; I was fascinated by the organizing of the 1950s and 1960s in a stew of uncertainty, where different folks proposed different strategies, sometimes at the last minute. People marched out the door of Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma in 1965, for example, and faced whatever horrors Sheriff Jim Clark aimed at them. Time and again, churches and their congregations held mass meetings to sing, sweat, pray, and develop non-violent tactics to counter white racism and violence. In addition to Bethel and Brown, we visited Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Dexter is right down the hill from the Alabama State Capitol, which is a jarring juxtaposition, demonstrating a different kind of leadership. On its front steps, the Capitol features a brass star to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, as well as a statue of him. A massive Confederate monument rises next to the Capitol. The “Lost Cause” has a powerful presence still, with statuary protected by the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act of 2017. White supremacy never gives an inch.

Arts in the Movement

One aspect that Phillips doesn’t discuss is the role of the arts in movement organizing. Our pilgrimage had the great good fortune to have Arnaé Batson on staff to lead us in song. Leaving the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (the lynching memorial) in Montgomery, Arnaé sang “Wade in the Water” to us on the bus, and later: “There is a balm in Gilead/ to make the wounded whole; there is a balm in Gilead/ to heal the sin-sick soul.” Her voice and those songs helped us transition to the next powerful experience. On many occasions, on and off the bus, she energized us and inspired us with music. While singing, you are breathing and breathing helps manage the intense emotions about white impunity and Black loss.

Each morning on the bus as we pulled out, Janice Marie Johnson, the co-leader, read short poetry or other reflective offerings that set the tone for the day: poems by Howard Thurman, Naomi Shihab Nye, Qiyamah Rahman, and Hope Johnson, among others. These helped expand our spirits to take in the injustices of voter suppression, land theft, housing discrimination, segregation in nearly every sphere and education denied. These conditions continue; Gov. Kay Ivey in 2021 signed a $1.3 billion bill to build two new prisons. A second bill, signed in 2024–the CHOOSE Act–creates a voucher-like system so that families can get up to $7,000 in tax credits toward education expenses at non-public schools. Guess who gets left behind? Guess who ends up in those prisons? As Rev. Peter Morales wrote, and Janice shared: “Help us take our history into our hearts as well as our minds. Open us, so that we can feel our past live in us—the joy, the disappointment, the passion, the pain, the hope. Let the past, all of it, live in the core of our being.”

The Long Game

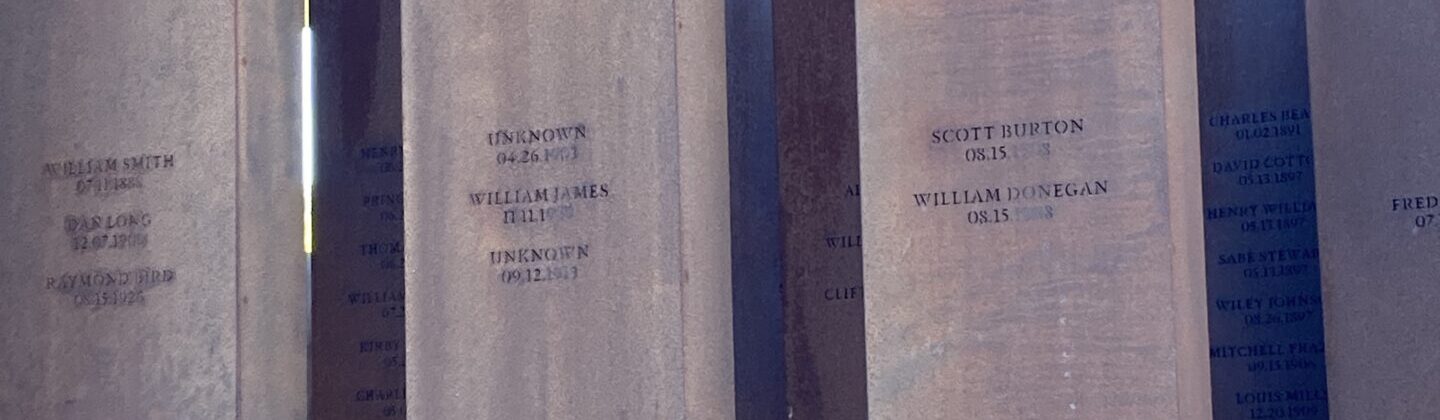

While we were in Alabama there was a full moon, a supermoon at that. While we didn’t have much time out-of-doors, the moon shone in its glory. Inside the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, the light was low–reminiscent of moon glow–while the multi-media displays powerfully conveyed truths about enslavement, Black codes, Jim Crow, and mass incarceration. There was visual art there, too, with works by Sandrine Plante, Sanford Biggers, Elizabeth Catlett, Hank Willis Thomas, and more. The artfully spotlit Community Remembrance Project–a wall of jars of soil collected from all over the country at the sites of lynching–tied the lynching memorial to the museum and, in turn, to the communities that are documenting their roles in this murderous practice. There are 56 documented lynchings in Illinois.

So, here we are for the long game, as Phillips names it. We learned about so many thwarted efforts for justice. Examples: In 1868, John Willis Menard of Louisiana was the first Black man elected to the US House of Representatives, but Congress voted to deny him his seat. Between 1882 and 1968, nearly 200 anti-lynching laws were introduced in Congress and failed to pass; finally in 2022, President Biden signed the Emmett Till Anti-lynching Act, making lynching a federal crime. Time and again, civil rights activists have worked full-tilt for change and were met with a shocking array of violent and bureaucratic responses. But they persisted. The pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Rev. Vernon Johns, a predecessor of Dr. King’s at Dexter, was known for his saying: “If you see a good fight, get in it.” Indeed.