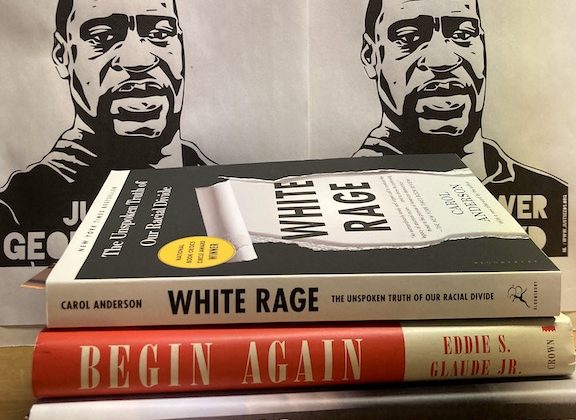

In Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own, Eddie S. Glaude, Jr., quotes a July 1968 interview with James Baldwin, in which he addressed the editors of Esquire magazine: “[Y]ou have a lot to face….All that can save you now is your confrontation with your own history…which is not your past, but your present.” (68) Nicolas Lampert’s portrait of George Floyd in the poster above helps me confront my history.

White-identified United Statesians like myself indeed have a lot to face. Glaude’s challenging book states: “Make the suffering real and force the world to pay attention to it, …understand it as the inevitable outcome in a country that continues to lie to itself.” (54) I agree with Glaude that the present-day overt and subtle enactments of racist cruelty and hate belie our supposed commitment to a multiracial democracy. This lie–that white supremacy does not poison our structures and relationships–has an enduring legacy and an amazing resilience, cropping up in many settings and forms, stubbornly thwarting our futures and killing people’s hopes, literally and figuratively. In my effort to confront my own history and present, and to try to counter the lie that many people in the United States continue to hold, I am reflecting on photographs from my family’s past that resonate today.

My father, Don Irish (1919-2017), was a sociologist who taught at Hamline University in St. Paul from 1963 until his retirement in 1985. One experiential short-term course he taught at Hamline was called “Deep South.” It was an interracial road trip with undergraduate students through parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia, which he led three times in the 1970s and 80s. How those trips were for the students, I don’t know. I can only guess that for Black students, the experiences of visiting places of racist violence would have been really difficult and that the white students and my white father may have made it worse for them. But that is only my guess, based on my own naïve and likely-detrimental presence in the South in the 1960s. (See Layla F. Saad’s Me and White Supremacy [2020] and the sections on white fragility, silence, exceptionalism, superiority, and saviorism, for starters.)

Dad took this photograph  of gated and fenced school grounds and buildings in Jackson, Mississippi in May 1973. The words on the gate, “Council School,” leave out an important identifier: “White Citizens.” White Citizens Councils (WCC) emerged after the 1954 Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision that mandated school desegregation. The first WCC was organized in July of 1954 in Indianola, Mississippi (about 100 miles north of Jackson, MS), and spread rapidly. According to a 1956 article, memberships in WCCs numbered 300,000. “Council schools” were among white people’s responses to the May 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision, when white families pulled their children out of public schools in order to avoid integration. In 1964, the WCC opened its first so-called private academy in Jackson, providing a model for private school education throughout the South.

of gated and fenced school grounds and buildings in Jackson, Mississippi in May 1973. The words on the gate, “Council School,” leave out an important identifier: “White Citizens.” White Citizens Councils (WCC) emerged after the 1954 Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision that mandated school desegregation. The first WCC was organized in July of 1954 in Indianola, Mississippi (about 100 miles north of Jackson, MS), and spread rapidly. According to a 1956 article, memberships in WCCs numbered 300,000. “Council schools” were among white people’s responses to the May 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision, when white families pulled their children out of public schools in order to avoid integration. In 1964, the WCC opened its first so-called private academy in Jackson, providing a model for private school education throughout the South.

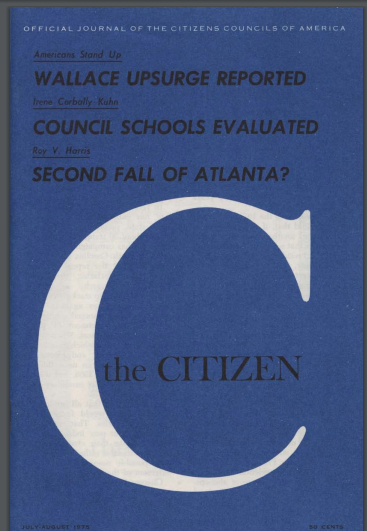

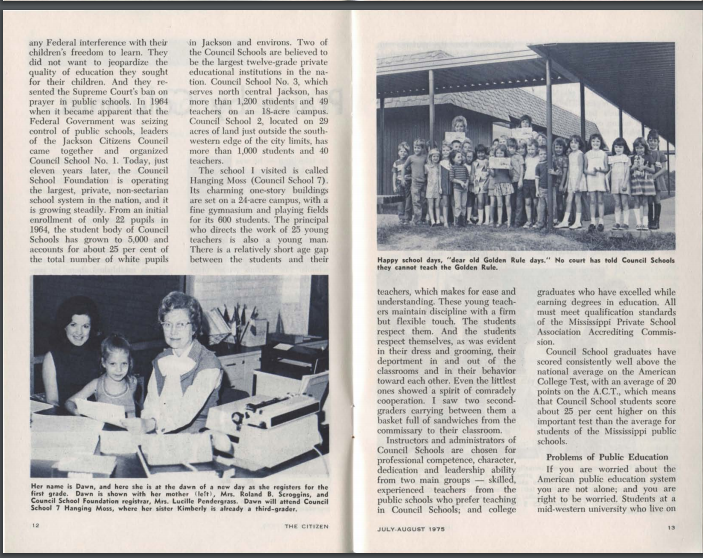

My father photographed the Hanging Moss School from outside the gates in 1973, two years before Irene Corbally Kuhn wrote a glowing report in the White Citizen’s Council publication, The Citizen. The magazine cover does not indicate that this is a publication of the White Citizen’s Council. The page spread from the July/August 1975 issue of The Citizen shows staff and students at Hanging Moss School. In 1975, this publication reported that “the Council School Foundation is operating the largest, private, non-sectarian school system in the nation, and it is growing steadily. From an initial enrollment of only 22 pupils in 1964, the student body of Council Schools has grown to 5,000 and accounts for about 25 per cent of the total number of white pupils in Jackson and environs.” Here’s the thing: these Council schools were not “private” because they syphoned public funds intended for public schools into the Council schools. For example, “[i]n 1964, at the Council’s urging, the Mississippi legislature passed legislation appropriating $185 per child in vouchers for private school tuition and allowing the free use of state textbooks in private institutions…. Although these vouchers were eventually ruled unconstitutional, the availability of public funding encouraged schools to open and provided a crucial financial base in their tenuous early years.” (Fuquay, 164)

White Citizens Councils (WCC) focused on economic and social oppression of Black people, although there was certainly overlap in approach and membership with the physical intimidation and violence of the Ku Klux Klan. (The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King in 1956 described WCC as the modern KKK. ) Medgar Evers, the chairman of the Jackson, MS, chapter of the NAACP, was assassinated by a member of a White Citizens Council in 1963. WCCs included the business elites, who ensured that anyone supporting Black civil rights was barred from employment, housing, and bank loans, if they weren’t outright murdered or maimed. Mississippi’s Senator James Eastland was described as a “patron saint of the Councils” and they got plenty of state-sanctioned support. (Also, Stein, 21) In 1985, the White Citizen’s Councils transformed into the Council of Conservative Citizens, and remains on the watchlist of hate groups maintained by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Carol Anderson in White Rage noted that Mississippi declared Brown “unconstitutional and of no lawful effect within the territorial limits of the state of Mississippi.” (79) The 1954 Brown decision was a landmark to be sure, building upon a series of court cases from 1935 into the 1950s. But despite efforts to counter inequality, white supremacy “deliberately produced a sprawling, uneducated population that would bedevil the nation well into the twenty-first century.” (70) White state and local officials used legal and illegal means to ensure that education for African Americans remained staggeringly insufficient: “overcrowded classrooms, decrepit school buildings, inadequate numbers of textbooks, schools lacking libraries, cafeterias, gymnasiums,” and no indoor plumbing. (Anderson, 69) What Anderson’s chapter, “Burning Brown to the Ground,” makes abundantly clear is that education for Black people in the U.S. has been egregiously unequal for a very long time. 2020 does not look much different than that depicted in my dad’s photo of 1973.

This inequality is and has been unacceptable. We must end white supremacy. As Glaude wrote: “To say then that the idea of white America is irredeemable is the equivalent of removing the stone that keeps our sense of ourselves in place. Without the idea, the whole house comes tumbling down. But if we don’t rid ourselves of the idea of white America, we seal our fate.” (81) Glaude claims that while the idea of white America is irredeemable, we people are not necessarily so. Of course, I want to believe that.

While I am committed to organizing and activism against social wrongs, I also believe in uncomfortably reflecting on the status quo and my roles in it. That creates an uneasy tension, for sure. Claudia Rankine in Just Us poses this challenge [to me, it seems!]: “What if you’re the destruction coursing beneath/your language of savior? Is that, too, not fucked up?” (9) Yes, yes, that is really fucked up. So, what is a white, middle-class, older woman to do? Keep facing the past and present, checking my life and assumptions, feeling the rage, and trying to thoughtfully respond to what’s happening. As Glaude wrote: “This history is inseparable from the landscape and built environment of the country.” (70) There are no shortages of places to start, or ways to continue undermining white supremacy.

An example of one strategy to enact what Glaude suggests—”Make the suffering real and force the world to pay attention to it”—is artist Seitu Jones’s memorial portrait of George Floyd, who was murdered by police in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020. Jones created #blues4george, a stencil that people could download from his website and place a portrait of Mr. Floyd in various locations as a reminder, a witness, and a prod to anti-racist actions. #Blues4George claims space in environments where Black people are not seen by white people, or are seen as threats. Thank you, Seitu Jones. Say their names. See their faces.

Resources

Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (Bloomsbury, 2016).

Kate Ellis and Stephen Smith “State of Siege: Mississippi Whites and the Civil Rights Movement” (accessed Aug 31, 2020)

Michael W. Fuquay, “Civil Rights and the Private School Movement in Mississippi, 1964-1971,” History of Education Quarterly 42: 2 (Summer, 2002), 159-180.

Eddie S. Glaude, Jr., Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and its Urgent Lessons for Our Own (Crown, 2020).

Claudia Rankine, Just Us: An American Conversation (Graywolf Press, 2020).

Layla F. Saad, Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor (Sourcebooks, 2020)

Waltraut Stein, “The White Citizens’ Councils,” Negro History Bulletin 20:1(October 1956), 2, 21-23.