My parents, my two older sisters and I lived in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, between 1960-1963. I was in third to fifth grades. During our years there, we marched in protest of segregated restaurants, movie theatres, and drugstores, boycotted segregated businesses, did voter registration drives, staged sit-ins, and were threatened by gun-wielding white men. The memories remain with me, though they are spotty, rather like patched pavement.

My mother, Betty Irish (1920-1985), who worked in the Alumni Office at the University of North Carolina (UNC), noticed the ways that Black students were identified with small letter codes on the back of individual 3×5 cards. These indicators undoubtedly helped control the approximately 60 Black students on campus in 1963. My father, Don Irish (1919-2017), a post-doctoral researcher in sociology at UNC, continued the civil rights work in which he’d been involved ever since his college days in Colorado. All five of us, practicing Quakers at the time, joined “the movement” and were not only involved with the Quakers but with the then-non-denominational Community Church, led by white activist-pastor Charlie Jones (1906?-1993).

Developmentally, at age 10, racism and segregation were black and white issues to me. Literally, there were Black and white people; racism and segregation were wrong; and my white family, in protesting white racism, was right. I perhaps sensed the ubiquity and tacit aspects of racism, but as a girl also busy with horseback-riding and painting lessons, my own whiteness was unmarked to me. I believe I attended Estes Hills Elementary School in 1960 (third grade), which was the site of “partial integration” that year, but I remember nothing of school. (Barksdale, 32) While we provided a room in our house to a high school girl from the Lumbee Tribe, I was completely clueless that we occupied Eno, Catawba and Shakori territories.

Well into adulthood, I held onto my childhood righteousness and rigidity. Business owners should welcome everyone, regardless of their bottom line. Decent housing should be available to all, despite private property owners’ biases. My white family, temporarily living in North Carolina after moving from Ohio, knew what was best for the local population. These unsubtle statements have a certain purity, but don’t center those most impacted by racism as the powerful organizers they were (and are.) I walked down an imaginary black and white road. The risk to me was minimal.

With hindsight of nearly 60 years now, I have been examining family photographs from those years. Since they were taken by my father, and this is my story, I do focus on our roles, knowing full well that our contributions were very modest and only possible due to the courage and sacrifice of so many, over decades. In addition to marches, our family picketed segregated properties; sometimes we went in small, integrated groups and sat down together in a restaurant, touching the napkins and silverware and sipping the water until we were told to leave.

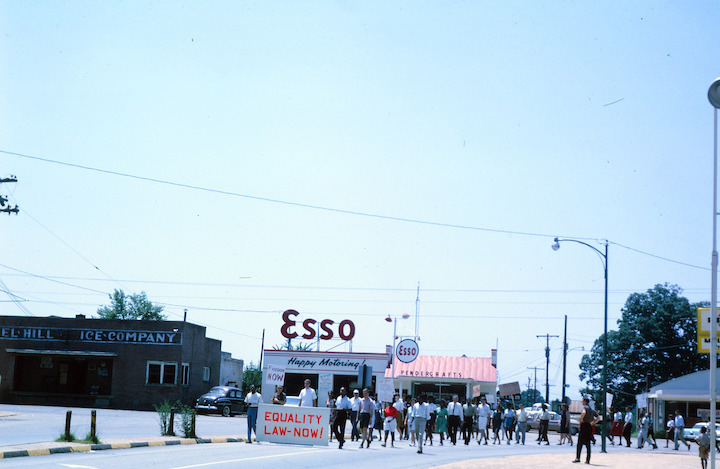

All three images that I have digitized are from a march down Chapel Hill’s main drag, Franklin Street, in the summer of 1963 in support of the Public Accommodations Law (PAL). This law would have banned racial discrimination in public places–hotels, restaurants, gas stations, theatres, and stores. John Ehle, who worked for the then-governor Terry Sanford, told part of the history in his 1965 book. Ehle recalled that the six-person Chapel Hill Board of Alderman held a town hall on May 23, 1963.

Professor Don Irish of the university sociology department, a member of the Mayor’s Human Relations Committee, …advised them to pass a public accommodations ordinance for Chapel Hill, a law which would assure reasonable service to all citizens in all public places. (41)

If it would have passed, it would have been the first public accommodations ordinance in the state, and in the South. By late May, the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Merchants Association “urged its members and other public businesses to end without further delay all discriminatory practices.” (Barksdale, 35) That was the word; deeds were much harder to accomplish. While 165 retail businesses were at least nominally desegregated by that summer, there were still a number that were not. On June 25, 1963, the Board of Alderman tabled the ordinance, 4-2. In January 1964, the Board of Alderman rejected a local PAL altogether, sparking more protests. (Barksdale, 40) Our family had moved to Minnesota by then.

After considerable debate, the newly-formed Chapel Hill Committee for Open Business (COB)—a grassroots effort to de-segregrate businesses and pressure city officials—decided to hold a march on May 25, 1963, in support of the PAL; at the end of that Saturday march, which numbered about 350 townspeople, the Rev. Charlie Jones spoke. According to Ehle, the mayor had been invited to speak but did not do so. I’m not sure who else might have spoken: certainly I would have wanted to hear from Harold Foster (1942-2017), who was then-chairman of COB and had led the march. Foster was a 19-year-old Black college student (at North Carolina College) and a native Chapel Hillian. Barksdale indicated that as a senior in high school, Foster had joined the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Committee for Racial Equality. (31) Ehle noted that “In 1960, when [Foster] had been in high school, he had picketed the Dairy Bar and the Colonial Drug Store; in 1960 and 1961 he had picketed the movie houses.” (35) This initial COB-organized march was the start of a summer of marches, held three times a week. Ehle quoted Pat Cusick, a white student organizer: “On Sunday afternoons we marched from St. Joseph’s Church to the Colonial Drug Store, where we sang freedom songs. Every Wednesday and Saturday we had a street march all the way downtown.” (62)

Based on Cusick’s description, I’m guessing that the images by my father are from a Saturday march through downtown Chapel Hill. Dr. Charlotte Taylor Fryar helped me identify the route (thank you). I assume in this case the marchers walked east to west. We were of various ages, and many of us were dressed formally (at least by today’s standards). The top photo, with greenery in the background, was taken at the intersection of Henderson and Franklin with the Battle building in the background.

The next image shows us marching in two lines past the Colonial Stores, west down Franklin Street, probably between Roberson and Graham Streets. The Colonial Stores, both in name and in building style, recalled the 18th century, when brickwork and broken pediments were typical of antebellum Georgian designs, both of Southern plantation mansions and Northern merchant houses.

The photo with the Esso sign appears to be the corner of Graham Street and Franklin Street, taken looking west towards Carrboro’s Main Street.

The first image shows Battle-Vance-Pettigrew Hall, on the UNC campus. “The Battle-Vance-Pettigrew Hall complex is named for Kemp Plummer Battle, president of the University during the white supremacist Redemption period, Zebulon Vance, governor of North Carolina during the Civil War and Redemption period, and James Johnston Pettigrew, brigadier general in the Confederate Army,” according to Yonni Chapman. The Battle Hall complex was a building from the same era (1912) as other monuments to the Confederacy, such as the bronze statue of “Silent Sam” (1913), both erected during another surge of virulent racism. George Lipsitz has written that these “spaces that reflect and shape the white spatial imaginary” have gone largely unnoticed. In order to secure freedom, “African American battles for resources, rights, and recognition not only have ‘taken place,’ but also have required blacks literally to ‘take places.’” The marches down the streets of Chapel Hill in the summer of 1963 were one of many instances of the “power of the Black spatial imaginary and its socially shared understanding of the importance of public space….” (52)

Michelle Alexander wrote in a recent opinion about “injustice on repeat”:

The politics of white supremacy, which defined our original constitution, have continued unabated — repeatedly and predictably engendering new systems of racial and social control…. No issue has proved more vexing to this nation than the issue of race, and yet no question is more pressing than how to overcome the politics of white supremacy — a form of politics that not only led to an actual civil war but that threatens our ability ever to create a truly fair, just and inclusive democracy.

Jesmyn Ward calls white supremacy “the great American Gorgon,” its “endless terrible laws and behaviors are its myriad heads, regenerating one after another. Rooting us in place with one glance, miring us in inequality. This is how we are frozen in stone.” And yet.

And yet people continue to march, sit in, stand up, speak out, and boycott many injustices. From 1963 signage reading “The customer is always white at Colonial’s lunch counters” to the recent condemnation of (and lawsuits over) the $2.5M payoff to the North Carolina Sons of Confederate Veterans by the UNC System for the “care and preservation” of the “Silent Sam” monument after it was removed from campus, people continue to resist the Gorgon of white supremacy. In addition to resistance, there are many people envisioning liberation and justice. I fervently hope we succeed in helping things become “less bad,” as the late Senator Paul Wellstone (1944-2002) said.

ADDENDUM: I found two more slides and digitized them.

◊

Many thanks to scholars Charlotte Taylor Fryar, William Sturkey and Anne Mitchell Whisnant for their help over email. They bear no responsibility for this content, however.

Resources

Oral histories available through the Marian Cheek Jackson Center Oral History trust are a trove: https://archives.jacksoncenter.info/

Michelle Alexander, “Injustice on Repeat,” New York Times (January 17, 2020) https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/17/opinion/sunday/michelle-alexander-new-jim-crow.html (accessed January 17, 2020).

Marcellus Barksdale, “Civil Rights Organizing and the Indigenous Movement in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1960-65” Phylon 47:1(1986), 29-42.

Charlene Carruthers, Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements (Beacon Press, 2018).

John Ehle, The Free Men (Harper & Row, 1965).

Charlotte Fryar, Reclaiming the University of the People: Racial Justice Movements at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (PhD dissertation, 2019).

Paul Gorski and Noura Erakat, “Racism, whiteness, and burnout in antiracism movements: How white racial justice activists elevate burnout in racial justice activists of color in the United States,” Ethnicities 0:0(2019), 1-25.

Charlie Kast, “Our History,” The Community Church of Chapel Hill http://www.c3huu.org/our-history.html (accessed January 17, 2020).

Brian K. Landsberg, “Public Accommodations and the Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Surprising Success?” Journal of Public Law & Policy 36:1(2015), 1-25.

George Lipsitz, How Racism Takes Place (Temple University Press, 2014).

Lowery, Malinda Maynor, Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South: Race, Identity, & the Making of a Nation (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Kate Murphy, Efforts to stop Silent Sam deal with Confederate group continue in multiple court cases,” The News & Observer (January 15, 2020) https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article239294798.html (accessed January 16, 2020)

Native Land https://native-land.ca/ (accessed January 16, 2020).

Daniel Pollitt, “Legal Problems in Southern Desegregation: The Chapel Hill Story,” North Carolina Law Review 43:4(June 1, 1965) http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol43/iss4/3 (accessed January 16, 2020).

Jim Wallace and Paul Dickson, Courage in the Moment: The Civil Rights Struggle, 1961-64 (Dover Publications, 2012).

Jesmyn Ward, “We Gather,” ACLU Magazine (Winter 2020), 35.

Anne Mitchell Whisnant, et al. Names in Brick and Stone: Histories from UNC’s Built Landscape http://unchistory.web.unc.edu/ (accessed January 16, 2020).