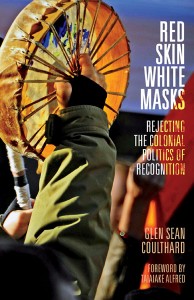

I am reading Glen Sean Coulthard’s Red Skin, White Masks (2014). One strategy I use when I am confused and trying to figure out next steps in politico-cultural action is to pick a book like Coulthard’s and find passages in it that help me understand what might be going on. Not that Coulthard is or should be the last word, or that he speaks for all First Nations people, or that he speaks for all Dene or Weledeh Dene people, but nevertheless there is much I am learning from him about Indigenous studies and colonial relations. And, Indigenous studies is at the center of my anguish about the undermining and disrespect of American Indian Studies and the unconscionable treatment of Steven Salaita by the University of Illinois.

I am reading Glen Sean Coulthard’s Red Skin, White Masks (2014). One strategy I use when I am confused and trying to figure out next steps in politico-cultural action is to pick a book like Coulthard’s and find passages in it that help me understand what might be going on. Not that Coulthard is or should be the last word, or that he speaks for all First Nations people, or that he speaks for all Dene or Weledeh Dene people, but nevertheless there is much I am learning from him about Indigenous studies and colonial relations. And, Indigenous studies is at the center of my anguish about the undermining and disrespect of American Indian Studies and the unconscionable treatment of Steven Salaita by the University of Illinois.

The University of Illinois is a colonial enterprise. A land-grant institution, it sits on stolen land, exploits resources inequitably, and profits from and reinforces a long history of racism. That could be said of many institutions and agencies in the United States, of course, but I am trying to name and describe the situation at my “home” institution since I feel so angry and alienated here. Coulthard writes: “Territoriality is settler colonialism’s specific, irreducible element….[C]olonialism [is] a form of structured dispossession” (p. 7).

We are not going to “get over” the Salaita debacle until we “get” some very fundamental problems with current university priorities. And these priorities are very slippery—Public Relations spins them in a mind-boggling number of ways. Coulthard again: “[A]ny strategy geared toward authentic decolonization must directly confront more than mere economic relations; it has to account for the multifarious ways in which capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, and the totalizing character of state power interact with one another to form the constellation of power relations that sustain colonial patterns of behavior, structures, and relationships” (p. 14). This convergence of relations seems like a brick wall, though assuredly there are cracks. One crack is that some have started to mis-behave: some are no longer acting like “colonized subjects.” This behavior appears rude and uncivil to those in power, and even to some of us watching from positions of less power.

Coulthard identifies time as a major axis along which Western views align; this aids in a linear assessment that declares many oppressions to be in the past. Viewed as a “legacy,” racism is far easier to discuss (even though we don’t even do that) than it is to face the attitudes and structures that support our institutions and lives in the present. Quoting Vine Deloria, Jr., Coulthard notes the gulf between these approaches: “‘When one group is concerned with the philosophical problem of space and the other with the philosophical problem of time, then the statements of either group do not make much sense when transferred from one context to the other without proper consideration of what is taking place.’” And yet the University seems to be uninterested in having Indigenous viewpoints ‘make sense’ within the institution, insisting that they be “reconcilable with one political formation—namely, colonial sovereignty—and one mode of production—namely, capitalism” (p. 66).

The University administration would like Salaita’s de-hiring and their egregious treatment of American Indian Studies to be in the past, so that “we” can move on. “[R]econciliation becomes temporally framed as the process of individually and collectively overcoming the harmful ‘legacy’ left in the wake of this past abuse,” writes Coulthard, “while leaving the present structure…largely unscathed…. In the context of ongoing settler-colonial injustice, Indigenous peoples’ anger and resentment can indicate a sign of moral protest and political outrage that we ought to at least take seriously, if not embrace as a sign of our critical consciousness” (p. 22).

In response to the Salaita de-hiring and its many implications, there have been valuable panels about academic freedom; important forums about Israel and Palestine; perhaps-useful listening sessions with faculty about governance. I acknowledge the hard work of organizing these opportunities for discussion, these small steps that are significant nonetheless. These events are also not frequent enough–despite people’s exhaustion at organizing and attending forums, panels and meetings–because time-consuming interactions around these issues are crucial to witness each other’s responses. At these events, may we feel the tension, experience the hostility, and stay with the moments of embodied discomfort. That is compassion: being with each other, often in pain. The constant “background field” for these University events is “the reproduction of hierarchical social relations that facilitate the dispossession of…lands and self-determining capacities” (pp. 14-15).

I want to stand with those unwilling or unable to “move on.” I want to “take seriously” the anger and resentment. I believe I must embrace these emotional and intersectional analyses. They point not only to negative conditions now, but also offer “invaluable glimpses into the ethical practices and preconditions required for the construction of a more just and sustainable world order” (p. 12). I don’t have any ready answers to what my “stand” looks like…yet.