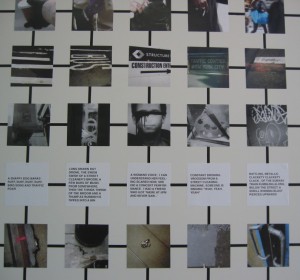

Stephen Willats is interested in both information networks and networks of meaning, each connected to real people in real locations. In Willats’ art, these networks intersect and overlap in complex ways; words, pauses, gestures, posture, and spaces between, all contribute both information and meaning to exchanges that are captured as “Data Stream: A Portrait of New York” (2011). For Willats’ one man exhibition at Reena Spaulings on East Broadway in New York’s Chinatown (The Strange Attractor, Sept 17- October 23, 2011), he created a long, two-sided wall for us to scan, or crane or squat to study. Ten rows of 57 images and texts of specific individuals make up a grid on this wall, recording parts of Delancey Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City in March 2011.

How does one relate to these images and data? Willats invites us to join him and co-create our own ontology; we perform our becoming in the gallery as we engage with the installation. Information as images and text is mounted down low, in the middle and up high; we parse it for ourselves, connecting to some bits and not to others. We study the photographs, rubbings, and words, seeing aspects of our lives captured visually, but only partially. We make our own meanings in relation to the complexity of a “strange attractor.” As time moves on, and/or new visitors and objects are juxtaposed, our constructed meanings shift again and again.

While my title above comes from Tiziana Terranova’s 2004 essay examining the cultural politics of information, Willats takes his title from the mathematical concept that cybernetician Heinz von Foerster (1911-2002) adapted to his concerns. A strange attractor is both a geometrical pattern characterizing a complex, chaotic system, and a dynamic object that is dissipating into chaos. The tension inherent in this dynamic pattern sustains a tenuous convergence akin to learning. For von Foerster, a “strange attractor” was one way to understand mid-century modern life, helping to define what is humanly knowable or not. Second-order cyberneticians like von Foerster aimed to generalize the feedback and control mechanisms from engineering and science to focus on the unpredictable, open relationships in society. Similarly, Willats’ colleague and mentor, Gordon Pask (1928-1996) and other scientists such as W. Ross Ashby (1903-1972), used the “black box” problem as a means of understanding not only what we know (epistemology), but also how we know it (ontology).

Scholar of science studies Andrew Pickering noted that “Black Box ontology is a performative image of the world. A Black Box is something that does something, that one does something to, and that does something back—a partner in, as I would say, a dance of agency.” Willats and his collaborators, with recording devices, still and video cameras, performed together up and down New York streets on two cold and wet days last March, creating multiple views of the city that, in turn, help us see and understand the give-and-take between objects and people in new ways.

Pickering has written brilliantly about the ontology of cybernetics, which is key to Willats’ art: “[C]ybernetics stages for us a vision not of a world characterized by graspable causes, but rather of one in which reality is always ‘in the making,’ to borrow a phrase from William James.” Second-order cyberneticians and artists like Willats recognize both the impossibility of ever fully observing each other from within their own embodied selves, and the significance of observing social systems within which individual minds and bodies perform. The contingency and opacity of relationships among ideas, material objects and observers is ever-present in what is being observed, stressing the “in the making” and performative aspects of our interactions, in other words, the resilience of meaning(s).

[1] Tiziana Terranova, “Communication beyond Meaning: On the Cultural Politics of Information,” Social Text [Technoscience] No. 80 (Fall, 2004): 52; Paul Pangaro, “The Past-Future of Cybernetics: Conversations, von Foerster and the BCL,” in An Unfinished Revolution? Heinz von Foerster and the Biological Computer Laboratory | BCL 1958-1976, Albert Mueller and Karl H. Mueller, eds. (Vienna: Edition Echoraum, 2007): 164.

[2] Andrew Pickering, The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010): 20, 19.